A Day to Save a Life

It was late Sunday night when I received a call from the County Commissioner of Uror. He was asking if we could respond to a rape case, the survivor had arrived in his compound that same day. My reply was, “We will, but not at this time, we will come tomorrow morning.” We are based in a deep-field location that is subject to frequent insecurity and traveling out at night would put the whole team at risk. So we would have to wait for the daylight.

It was late Sunday night when I received a call from the County Commissioner of Uror. He was asking if we could respond to a rape case, the survivor had arrived in his compound that same day. My reply was, “We will, but not at this time, we will come tomorrow morning.” We are based in a deep-field location that is subject to frequent insecurity and traveling out at night would put the whole team at risk. So we would have to wait for the daylight.

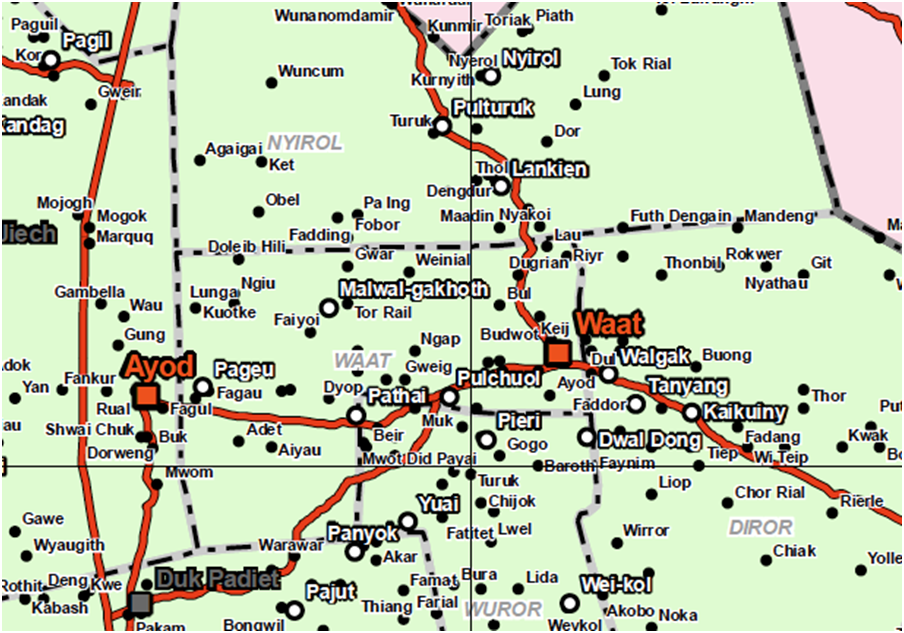

In the early hours of Monday morning I prepare to respond to the call of the Commissioner. The night before I was very aware of the many activities we had planned already: a discussion meeting with the community leaders in Pieri (one of the Payams of Uror) and security assessments in Patahi and Pulchol (also in Uror). In my mind I thought of how we could respond, by possibly dividing the team into two or three so that we can meet all of our commitments. It is impossible however, as we only had one vehicle to ferry us in responding to this high priority case. Therefore, I decide to go with the team of three to respond and we leave the rest of the team to facilitate the cancellation of today’s meetings with key actors.

Oftentimes we have to make difficult decisions like this about programming. If we take on something new that means we cannot do other things. We have to ask ourselves, “Is this something needed immediately to prevent violence or save lives?” If the answer is yes, that is what gets prioritized.

As we move out of our compound to meet our survivor in a place called Pathai, we can already see the way is muddy and slippery from the hard rainfall the night before. I begin thinking now of how bad it will be further along on the journey; Pathai is around 40 kilometers away from our base in Waat.

During the dry season this journey takes one hour each way. However, with the rainy season there is a lot of difficulty created, as the road is made of dirt with no concrete or gravel. The rain has created pools of water and mud along the way and our driver has to put the vehicle on a four-wheel drive. Otherwise, we will get stuck on the the slippery and muddy road. Our driver goes very carefully because we don’t want to take a chance on losing the opportunity to save a life. We move slowly but surely, stopping and checking the muddy part of the road. We have to make sure that it is safe for us to move forward.

The Commissioner calls me again to make sure that we are coming because it is getting late. Finally, we arrive at the compound where the County Commissioner is. The journey took us upwards of two hours. It is my first time meeting him, thus we introduce ourselves. The previous Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP) Waat team leader had met with him so he was already familiar with our work. When this case happened the Commissioner knew he could call us. After the introductions, the Commissioner introduced us to the survivor, Mary*, who was being cared for by a female soldier while waiting for our arrival.

Mary told us that she was beaten and raped by what she describes as more than 20 armed men. Mary, not speaking and barely able to walk, was found by passers-by who brought her 40 kilometers to the Commissioner’s office. We can see she is weak and injured. She is not eating or drinking, it seems this is because she was choked during the attack and now she is struggling to swallow. We know it is important for Mary to receive medical treatment within 72 hours because treatment for sexual violence survivors includes post-exposure protocols which are only effective within that timeframe. However, we do not know how long it has already been since the attack. Because time is not on our side, I ask the Commissioner if we can move right away. He agrees. The road is very bad but we need to bring Mary to the clinic as fast as we can or we will lose her. We put her into the car, bid our goodbyes and set off.

These Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV) cases happen too often in the current conflict. Women are frequently at risk since they have to travel long-distances alone on foot, through insecure conflict areas, in order to get food for their families. NP does everything we can to help women in staying safe and to preventing incidents like this. When we cannot help prevent these incidences, we help to ensure treatment is reached.

These Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV) cases happen too often in the current conflict. Women are frequently at risk since they have to travel long-distances alone on foot, through insecure conflict areas, in order to get food for their families. NP does everything we can to help women in staying safe and to preventing incidents like this. When we cannot help prevent these incidences, we help to ensure treatment is reached.

The MSF (Médecins sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders) hospital where we need to bring her is more than 100 kilometers away in a town called Lankien. We ask MSF if they have a plane to take the woman but the airstrip is not landable due to the heavy rains. At the start of the journey, the driver lets me know that we need more fuel because traveling on the muddy road consumed most of our fuel. We consider our options, which are returning to our NP compound in Waat or heading to another international non-governmental organization called Tearfund to borrow fuel. We choose the Tearfund option, as it is closer. Even the most simple of actions in places as underdeveloped as northern Jonglei State are complicated and have to be thoroughly planned.

At first, we all felt good because we had a plan and we were helping someone, but then everyone’s emotions changed. We all feel frustrated. We are running against time, we are low on fuel and we are negotiating with the muddy and slippery roads. Mary is also clearly in pain and in need of immediate help. I feel like we are not helping anymore, this trip is going so slow and every moment counts. My anxiety builds up, as more and more time goes by. I feel really very bad seeing how much pain Mary is in and we are feeling helpless because there is no way to make the travel faster. I can’t help but think if only I was a superhero, then we will be there by now and Mary would get the help she needs.

Finally, we reach the Tearfund compound where they give us two jerry cans of fuel and we start running again. In the first hour we are running normally. The road is dry and it looks very promising that we will be able to reach to the hospital on time. We are told that the road is dry up to the MSF hospital, however an hour into the journey, it is gets muddy again and we slow down. Negotiating the muddy part of the road is no easy task for our driver and I realize there is no one close by who can get us out if we get stuck. These are the challenges we face everyday in the South Sudan rainy season, trying to reach people who need our support but having so many obstacles even in traveling small distances. We need to reach to the hospital; we have been now traveling with Mary for four hours.

After 30 minutes of making little progress, we change approaches and drive through the thick bushes to avoid getting stuck in the mud. When we rejoin the road we are still eight kilometers away from the hospital, which is starting to feel like another 100 kilometers more. The road is so bad we leave it again to drive through the bush, but still it takes us more than an hour to cross these last few kilometers

Finally we reach the hospital. We have been driving with Mary for seven hours. The medical team, already informed of the case, takes her quickly to be treated. We leave the hospital after making sure that she is safe and receiving medical attention. Our driver is now exhausted and so I drive us the three hours back home.

We finally rest and enjoy our dinner, calling it a day, for tomorrow will be another challenge.

By Zandro Escat Team Leader in Waat (South Sudan)