"We used to simply let our leaders handle conflict resolution on their own"

Source: European Peacebuilding Liason Office

Original link: "Nonviolent Peaceforce in South Sudan" in 'Peace' in the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus, (page 18)

In response to ongoing needs in Upper Nile State, NP and SI joined forces to partner on a project funded by the European Union (EU).

Martha, a member of an advisory board, shared that “we used to simply let our leaders handle conflict resolution on their own, but after training, my fellow women and I realized that we can make significant contributions to conflict resolution and violence prevention in our communities.”

Overview

Violent conflicts, protection risks, and the needs of civilian populations emerge and exist within complex, interlinked systems. This is the case in Upper Nile State, South Sudan – a region that faces poverty, state fragility, forced displacement, and climate change, and where responses to these challenges must recognize the ways these forces shape and are deeply interlinked with violent conflict and humanitarian needs. This case study explores one program Nonviolent Peaceforce (NP) is currently implementing in collaboration with communities and Solidarities International (SI) in Upper Nile State. The program aims to work across silos and integrate humanitarian action with longer-term development and peacebuilding work to meet civilian needs in dignified and sustainable ways.

In Upper Nile State, communities face systemic challenges across several fronts. Despite national efforts to address conflict dynamics, such as the Revitalized Agreement on the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), communities in Upper Nile continue to face violence at the sub-national and intercommunal levels, climate shocks related to flooding, mass displacement, and conflict over access to resources. In 2021, extreme flooding in the region led to mass displacement of households, loss of livelihoods, rises in extreme food insecurity and malnutrition rates, and the destruction of critical infrastructure – including for water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). Communities in Upper Nile are living in remote locations, with very limited access to services and markets, particularly for those who reside outside of the Malakal Protection of Civilians (POC) site. This includes limited access to clean drinking water, in conjunction with open defecation due to lack of latrines.

The extreme food insecurity the region faces has contributed to major protection concerns and risks, including tensions and violent conflict over resources, child labor, and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Crucially, systemic shocks have exacerbated conflicts between different communities, often along clan and subclan lines. Communal tensions have been ongoing between Shilluk, Dinka Padang, and Nuer communities. These tensions have often escalated into open violence, including SGBV, injuries, and civilian deaths.

In response to ongoing needs in Upper Nile State, NP and SI joined forces to partner on a project funded by the European Union (EU) that aims to strengthen community resilience to external shocks and access to resources over the long term, as well as to prevent potential conflict arising related to resource scarcity, whilst simultaneously providing support to address immediate civilian protection and humanitarian needs.

The project animates the HDP nexus in two primary ways. The first is as an overarching ethos of project design, where the project outcomes and theory of change themselves integrate different areas of need and expertise: bringing a conflict sensitivity and peacebuilding lens to WASH implementation; addressing access to material resources as a way of strengthening the protective environment and preventing violence.

A primary example of realizing these goals to date is how the partners and communities themselves have collaborated across WASH, food security and livelihoods (FSL), and protection. SI plan to rehabilitate 9 water sources across 3 counties as part of the project, as well as to distribute livelihood kits (such as those that support main cereal crops, vegetables farming, and fishing activities). Unlike conventional programming, where sites or distributions might be selected based more on most acute needs, access, and/or cost considerations, the project integrates this decision-making with protection concerns, prioritizing areas more prone to conflict over access to water and resources.

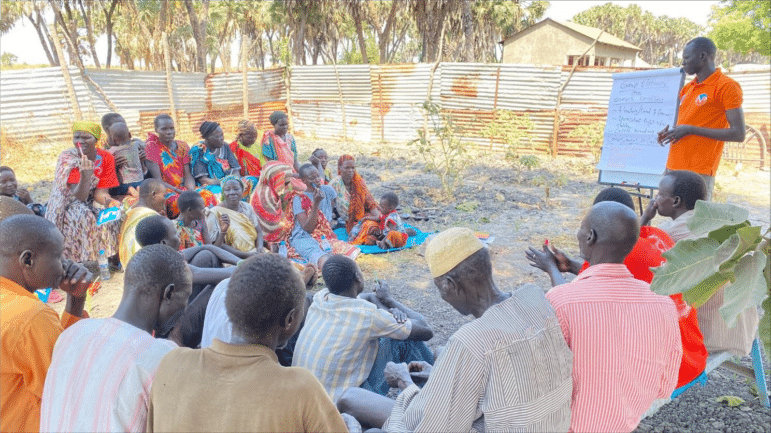

To understand protection risks and needs of communities and how they are shaped by access to resources, teams held joint meetings with community members and leaders, working with them to identify priorities and ensuring they have opportunities to shape the project from the outset. Communities have now formed inclusive Advisory Boards that meet monthly. Each payam’s advisory board is made up of a chief, local religious leaders, youth leaders, women leaders, and prominent community representatives, including people with disabilities, from a range of different community groups.

The purpose of these boards is not only to shape project implementation and provide frequent feedback on program effectiveness but also to provide spaces for communities to plan and work together over the longer term toward sustainable peace and development. Martha, a member of an advisory board, shared that “we used to simply let our leaders handle conflict resolution on their own, but after training, my fellow women and I realized that we can make significant contributions to conflict resolution and violence prevention in our communities.”

In addition, the project supports Women’s Civic Action Groups who work directly in their communities across protection, WASH, and FSL interventions. The goal of these groups is not only to strengthen intracommunity capacity and knowledge across these areas, but also that the groups become self-sustaining over time, ensuring an effective transfer of skills and contributing to the localization of support. In addition, the groups act to support social cohesion over the longer term by inviting women from different clans and sub-clans to work together. In Baliet and Melut, Nuer, Dinka, and Shilluk women work alongside each other to identify and respond to key tension points.

Importantly, in addition to the external project goals and ethos itself, the secondary way that this project animates the HDP nexus is through practices of operation internally, where NP and SI work with intentional collaboration at all levels – from teams on the ground in Upper Nile State, through to management levels in Juba. The intent of this project is to interweave the organizations’ respective areas of expertise – NP from peacebuilding and civilian protection perspectives, and SI from humanitarian and development angles – to work together to implement a much more integrated and effective intervention.

Good practices and lessons learned

• Start with communities: The HDP nexus can’t just be about humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding organizations. By recognizing and situating local communities themselves as primary leaders and stakeholders in interventions, particularly those most marginalized from decision-making such as women and youth, integration of HDP nexus thinking is much more likely across sectors. At the same time, the project shows how organizations can assist communities to access international coordination mechanisms, and simultaneously draw international actors into spaces where communities are already making essential contributions to relief, peace, and development. Closing the gap between international and local action is a parallel process that helps to close gaps between humanitarian, development, and peace work.

• Programming needs to be mutually reinforcing and integrated: This programming works because of the way it is integrated. It is designed to reinforce the strengths of each actor – NP, SI, as well as communities themselves. By layering different forms of expertise and knowledge and working together, we co-create a much stronger project. This is not just a matter of project design or by virtue of a consortia, but integration as a daily task: sharing updates, planning, and reporting together, coordinating logistics. This integration needs to occur on every level, from those on the ground to senior management.

• One project is not enough: HDP nexus principles have to be integrated across the humanitarian and peacebuilding sectors more broadly. When projects that don’t follow these principles occur in the same context (for example, when food distribution boats stop in a community they are not actually providing food aid to, or if there are not partners to refer to present in an area) this can have ripple effects and compromise community trust of service providers more generally. The more HDP programming is common across sectors, the more this can be avoided.

Key recommendations for the EU

• Institutional integration within the EU: The security situation in Greater Upper Nile is constantly changing, requiring nimble responses from partners. Unlike the support provided through DG ECHO, other EU instruments are not emergency funding mechanisms, and there are often barriers to programming with the level of flexibility required in this context. More integration between different EU services (and donor agencies in general) and instruments is required.

• Policy integration within the EU: Though the EU funds unarmed civilian protection work like that integrated into this project, and program managers know that this approach is effective, this has not yet translated at the policy level. Greater emphasis on the capacity and importance of civilian-led interventions is critical to implementing HDP nexus principles in ways that are sustainable and effective.

• Risk and creativity: In this case, the willingness of the EU to back a pilot project, to work out iteratively together what is working and what is not, and to follow the lead of communities is proving an essential ingredient in the project’s success. More appetite for risk, creativity, and commitment to programming that is context-specific and community-based is an important pathway forward.